Trailblazers: Stephen Mather

From time to time, I will be highlighting some remarkable people, both contemporary and historical, who’ve had a significant second half–what we call a Second Rodeo. This is not to hold them up as role models, but to inspire and share examples from which we can all learn.

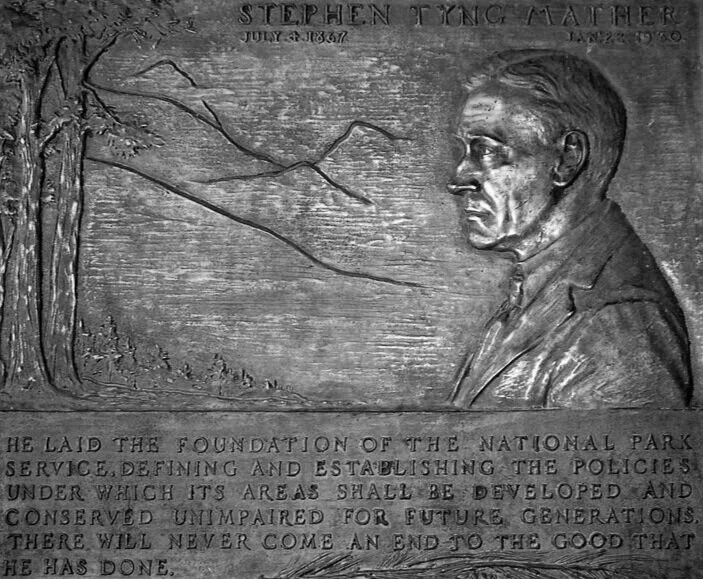

Not long ago, my wife and I got around to watching the Ken Burns documentary on the national parks here in the United State. That’s when I first heard about Stephen Mather. Until then I was not familiar with him or his role in history. Just a few weeks later, we were at Haleakala National Park and there in front of the Visitors’ Center we saw a memorial plaque–dedicated to Stephen Mather.

I have since learned that you’ll see this plaque at most of our National Parks, Monuments, Historic Sites, UNESCO Biosphere Reserves and World Heritage sites. The caption underneath the bas-relief portrait reads, "He laid the foundation of the National Park Service, defining and establishing the policies under which its areas shall be developed and conserved unimpaired for future generations. There will never come an end to the good that he has done."

As I read it, that last phrase really hit me in the feels. “There will never come an end to the good that he has done.” That’s what I want for myself, and for each of you–an enduring legacy.

Mather was born just after the Civil War and died just before the Great Depression. Born into wealth, he made his own fortune from the mining of borax, a popular household cleaning agent of that day. His wealth gave him the opportunity to pursue numerous philanthropic opportunities, but none of them really engaged in a meaningful way. It was while traveling in Europe with his wife that he rekindled a dormant passion for nature and conservationism that became the catalyst for the rest of his life.

Upon returning home to California, Mather joined the Sierra Club, and his friendship with the legendary John Muir further deepened his convictions about conserving America’s greatest national treasures before it was too late. In his travels to the few national parks then in existance, he was dismayed at their deep states of deterioration and disrepair. Some were being openly pillaged for profit by the very people charged with protecting them. Mather was determined to find the funds to properly protect them from being “loved to death.”

At the age of 49 he sold his half of the mining company to his partner. Not long after that began using his persuasive influence to find money for Park support, eventually going to Washington as assistant secretary of the Interior. There he lobbied to establish a bureau with sole responsibility for the handful of national parks and monuments in existence. Administration for these lands fell under various agencies, all of whom had bigger priorities.

In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed a bill authorizing the National Park Service. All the parks and monuments were then consolidated under the NPS. A year later, Mather was appointed as its first director, a position he held for thirteen years. With virtually no budget, he hired fellow Sierra Club member, Horace Albright, to be his assistant, paying Albright’s salary out of his own pocket for years because there was no budget for staff.

Mather’s tenure was phenomenally successful. He had a knack for bringing political enemies together to acquire new lands. He convinced presidents of both parties that the national parks would be their biggest legacies. He persuaded his wealthy friends to acquire, then donate valuable parcels of land when the federal budget was insufficient. On top of that he was able to convey the importance of the National Park System in language that ordinary Americans could identify with, garnering public enthusiasm to the cause. By the time he left his position, the park system included 20 national parks and 32 national monuments. More importantly, Mather created the criteria for identifying and adopting new parks and monuments, most of which are used to this day.

One of Mather’s most significant gifts to our nation was the ability to select and empower remarkably competent superintendents for our national parks. It was the integrity and leadership of these stewards of America’s resources that turned the tide of inevitable destruction. Mather’s generosity was legendary, often treating the superintendents and their families to extravagant meals that would have been far beyond their means to enjoy on their own. And they loved him. Not just for his generosity but for the faith and trust he placed in them. While many leaders accomplish significant things, in my experience few achieve them while remaining as beloved as Stephen Mather.

If we didn’t know the rest of the story, we might simply chalk up his success to the unholy trinity of money, power, and personality. But Mather suffered greatly from what we know today as bipolar disorder. On several occasions he became so debilitated that he had to be hospitalized for extended stays. It became apparent that he’d hired a capable man like Albright for just such occasions. Yet as soon as Mather was able, he would return to work with the same tireless optimism and passion he’d had before. To me, his willingness to persevere in the face of intense personal suffering–to pursue this great and glorious mission–is the most inspiring and motivating part of his story.

Who knows how long he might have served if a disabling stroke had not forced Mather’s retirement? He died just a year later, only 63 years old. Even as I share his story with you, I’m moved again at the scope of his impact. He could easily have been content to be just another wealthy industrialist pursuing a leisurely life with a few pet projects on the side. Who knows what might have happened to our national treasures if not for him? I’ve been obsessed with Second Rodeos for years now, and I know of few examples of an individual who experienced both success and significance at this level.

There’s so much we can learn from Mather’s example. It’s a perfect example of our model, living at the intersection of passion, skills, and need. I’m tempted to extract some principles; I think the better choice is to leave that to each of you. I don’t think there are universal principles because we’re all traveling our own road. It’s just nice to know that we don’t have to blaze a trail on our own. People like Stephen Mather can show us the way.

I’d love to hear how Mather’s story hits you. You can always leave me a message at our website or email me.

***

We depend on our readers to help us spread the Second Rodeo vision. If you found this article useful or interesting, could you please forward to a colleague or friend who might benefit from it?